Past Projects

Articles

This 2025 article analyzes Ottobah Cugoano’s argument against the type of moral wrongdoing of those who participated in the practices of the transatlantic slave trade and of enslavement. I will argue that Cugoano describes moral wrongdoing in a general and particular sense. In a general sense, Cugoano depicts a form of moral wrongdoing or behavior that applies to humanity as a whole and is essentially a state of selfishness in which reason is superseded by a “viciated imagination.” Selfishness is equated with drunkenness or stupidity. The imagination is erroneously used to invent reasons and justifications for one’s actions outside of concern for others. Cugoano describes the particular sense of wrongdoing that follows from his general observations, especially when he analyzes the specific practices of the traders, kidnappers, and enslavers in the transatlantic slave trade. These practices represent something exemplary because they demonstrate collective and coordinated efforts of moral wrongdoing. Cugoano describes the enslavers as a self-interested group of men outside of the bounds of civil society since they are not guided by “any human law or divine, except the rules of their own fraternity.” The paper will conclude by focusing on the philosophical and ethical dimensions of Cugoano’s descriptions of imagination and moral wrongdoing.

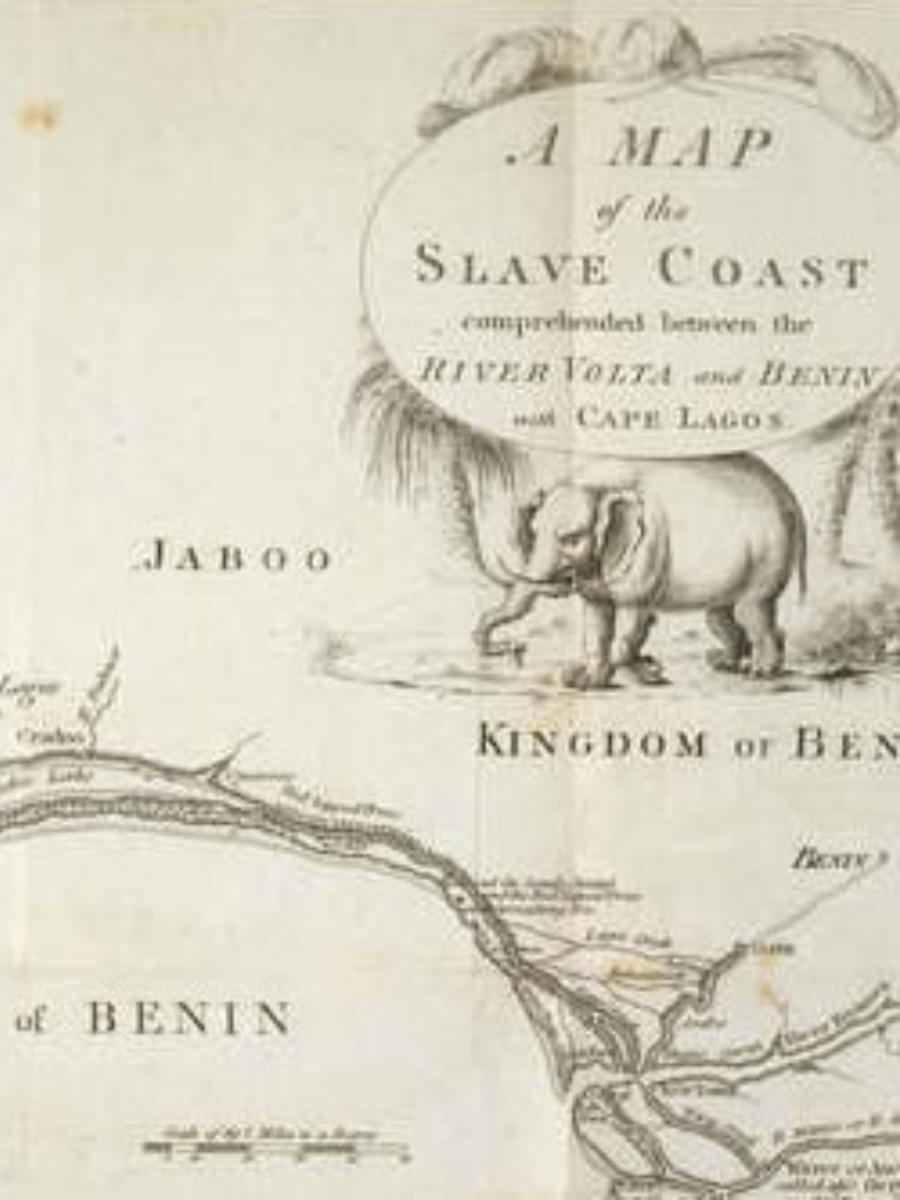

This 2024 article brings together the history of the Atlantic slave trade in the seventeenth century and Hugo Grotius’s treatment of slavery, war, and trade in the De iure belli ac pacis. In this paper I focus on the practices of slave raids during the trade in the 1630s through the 1640s in Central and West Africa. The practice of slave raids was often described and categorized by both Africans and Europeans as war or acts of war. I argue that given Grotius’s depictions of a solemn war, it is difficult to legally distinguish an intent to enslave in a raid from an act of war against an enemy nation.

This 2024 article on Ottobah Cugoano titled “Ottobah Cugoano on Chattel Slavery and the Moral Limitations of Ius Gentium” highlights the significance of his 1787 work Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787) in the history of philosophy by situating his abolitionism within the natural law tradition. I focused on Cugoano’s discussion of the moral conditions that could fully justify a lawful slavery under natural law in view of the distinction between ancient slavery and modern slavery. There, I argued that he establishes a notion of natural law that not only maintains moral preconditions in order to be recognized and obeyed, but also meets a social necessity to maintain society. In contrast to the existing scholarly literature, I contended that he treats natural law as more than just a rhetorical strategy of an eighteenth-century abolitionist text, for his argument strikes at the heart of the moral principles of natural law and contract theory in the history of philosophy, particularly as they relate to the forced enslavement of individuals.

Books

My current book manuscript Early Modern Women on War and Peace excavates the philosophical responses of early modern women to war and its catastrophic consequences. My analysis reveals the centrality of war to the development of early modern philosophy and the distinctive contribution that these early modern women philosophers make to thinking about this topic.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), the English Civil Wars (1642–1651 and 1688–1689), and the French Civil Wars or La Fronde (1648–1653) brought about unprecedented violence, destruction, and challenges to political institutions and authority. During this time of extreme and continuous violence, a renewed evaluation of human nature became pervasive within intellectual circles throughout Europe as philosophers attempted to rethink the basis for political stability, religious tolerance, and, most significantly, ending conflict and minimizing bloodshed. Thinkers such as Hugo Grotius, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Samuel von Pufendorf attended to the realities of perpetual warfare by transforming traditional ideas of authority and institutional organization, but they never questioned the role of war within the economic and social fabric of society; in particular, they never questioned its legitimacy.

The analysis focuses on Elisabeth of Bohemia, Mary Astell, Madeleine de Scudéry, Madame de Lafayette, and Margaret Cavendish as they respond to the wars of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, conflicts whose political instability as well as economic and social devastation directly affected them. All these thinkers had distinct responses to wars, but they agreed that war itself is not an inevitable condition and that its consequences can outweigh its legitimacy. These key observations, among others, distinguished their thought from the prevalent theories of just war, which treated war as an essential aspect of the human condition. This book project attends to how these female writers saw the problem of war: not in theories of self-defense but centrally as a question of political right and legitimacy.